Part of a series of brief artist biographies I wrote for Rhino.com in the spring of 2010 ...

Everyone who bought the Velvet Underground's first album in the 1960s ended up forming a band, while everyone who bought Big Star's first album in the '70s became a rock critic—or so the saying goes. Though they were beloved by critics, Big Star also influenced a new generation of bands in the '80s and beyond, from the Replacements, who sang "I never travel far / Without a little Big Star" on 1987's "Alex Chilton," to R.E.M., the Lemonheads, Teenage Fanclub, and Wilco.

The group got its start in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1971 when 20-year-old singer and guitarist Alex Chilton, having abandoned his role as teenage frontman for the Box Tops two years earlier, joined Ice Water, a trio consisting of Chris Bell (guitar and vocals), Andy Hummel (bass), and Jody Stephens (drums). Inspired by the Byrds and the Beatles, Chilton and Bell started writing songs together, and during a break in rehearsal one day at Ardent Studios, the new band decided to name themselves after the grocery store across the street.

When Big Star's debut album, #1 Record, was released in the spring of '72, critics raved; Rolling Stone's Bud Scoppa called it "exceptionally good" and praised the guitar work and harmonies on songs like "The Ballad of El Goodo" and "Feel." Unfortunately, a convoluted distribution arrangement between Ardent's in-house label and Stax Records prevented the album from reaching many listeners: when readers of those rave reviews went to buy #1 Record, it was nowhere to be found. The band's tongue-in-cheek name and their album's wishful title suddenly seemed like cruel jokes.

When a disillusioned Bell quit the band in late '72, Big Star appeared to be finished, but the following spring Ardent held a convention for rock journalists, and Chilton, Hummel, and Stephens agreed to perform. The enthusiastic response from Lester Bangs and other writers convinced them to give it another go.

Thanks to Chilton's love of Memphis soul, Radio City (1974) has a grittier sound than its predecessor, exemplified by the funky "O My Soul" and blues-tinged "Mod Lang." It also features "September Gurls," one of the defining anthems of power pop. Once again, however, Stax was unable to get the album into record buyers' hands.

Hummel bowed out and headed back to college, while Chilton and Stephens returned to Ardent Studios in the fall of '74 and recorded what eventually came to be known as Third, or Sister Lovers. By the time it received a belated release on the PVC label in 1978, Big Star was no more, but the resulting album was a masterpiece, filled with fragile love songs ("Nightime"), furious rockers ("You Can't Have Me"), and bleak ballads ("Holocaust").

On December 27, 1978, Chris Bell died in a car accident at the age of 27. He only released one solo single before his death, the achingly majestic "I Am the Cosmos," the title of which was used for Rykodisc's 1992 compilation of his post-Big Star recordings (Rhino Handmade reissued I Am the Cosmos in 2009 as a deluxe two-disc package).

Chilton went on to have an eclectic solo career, and Stephens was hired as director of A&R at a revived Ardent Records. In 1993 two students at the University of Missouri asked Big Star to reunite for a concert; to Stephens's surprise, Chilton said yes. With Hummel enjoying a career as an aerospace engineer, Stephens recruited Big Star disciples Jon Auer (guitar) and Ken Stringfellow (bass) of the Posies to fill out the lineup.

Big Star 2.0's performance was captured on CD as Columbia: Live at Missouri University 4/25/93, and the group continued to perform one-off reunion concerts throughout the '90s and the following decade, culminating in the first new Big Star album in 30 years, 2005's In Space. It was followed in 2009 by Rhino's four-disc retrospective Keep an Eye on the Sky.

Chilton died of a heart attack on March 17, 2010, three days before Big Star was scheduled to play at the South by Southwest festival in Austin, Texas. The concert was then refashioned as a memorial to the iconoclastic musician, with R.E.M.'s Mike Mills, the Lemonheads' Evan Dando, the Watson Twins, and even Andy Hummel paying tribute in song.

Friday, December 30, 2011

Thursday, December 22, 2011

kinda sorta book reviews for tweens and teens (i.e., stuff I read in my YA classes this year)

The Cay by Theodore Taylor (1969). Delacorte Press; 137 pages; adventure; ages 8-14; ISBN: 0-380-01003-8.

The Cay by Theodore Taylor (1969). Delacorte Press; 137 pages; adventure; ages 8-14; ISBN: 0-380-01003-8.Phillip Enright is an 11-year-old American living on the Dutch-occupied island of Curaçao during World War II. His father works for a local oil refinery, a target of German submarines that also happen to be torpedoing ships off the coast, and his mother decides that the island is no longer safe—she decides to take her son back home to Virginia. But tragedy strikes shortly after they depart when their ship is torpedoed as well; Phillip is hit in the back of the head with a piece of timber and blacks out during the evacuation, and when he wakes up he's on a raft with Timothy, a shipmate who rescued him from certain death in the water.

Timothy was born in the West Indies. He grew up with nothing, and doesn't know his own birthday. He and Phillip have nothing in common, but he will protect Phillip at any cost, and they must work together to stay alive, especially once they land on a small island, or cay, located in a forgotten part of the Caribbean that Timothy refers to as "the Devil's Mouth." A fast-paced, suspenseful story that provides poignant lessons on racial tolerance and the ties that bind all men together, The Cay almost dares you not to finish it in one sitting. It's a mesmerizing reading experience from start to finish.

Winner of a 1970 Lewis Carroll Shelf Award and the Jane Addams Children's Book Award that same year, though the latter was revoked five years later due to controversy surrounding the author's portrayal of Timothy, who speaks in a Creole dialect. For further reading, check out Taylor's 1993 sequel of sorts, Timothy of the Cay.

Iggie's House by Judy Blume (1970). Atheneum Books for Young Readers/Simon & Schuster; 117 pages; realistic fiction; ages 8 and up; ISBN: 978-0-689-84291-7.

Iggie's House by Judy Blume (1970). Atheneum Books for Young Readers/Simon & Schuster; 117 pages; realistic fiction; ages 8 and up; ISBN: 978-0-689-84291-7.Eleven-year-old Winnie's best friend from down the street, Iggie, has recently moved to Tokyo with her family. As Judy Blume's first novel begins, a new family is moving into Iggie's house—a black family, making them the first nonwhites in the neighborhood. Winnie's excited to make new friends with the Garber family's three children, Glenn, Herbie, and Tina, and show them she's not like other white kids, but her parents are less enthused, mainly because they can see the trouble around the bend that Winnie can't. And once neighborhood busybody Dorothy Landon starts up her own unwelcoming committee, tempers begin to flare on both sides of the issue.

Blume's YA debut shows her in full control of her talent, which blossomed even further as the '70s rolled on. She creates memorable characters like hotheaded Herbie, who confronts Winnie on her ill-advised "great white savior" role and in general speaks his mind like a grade-school prototype of TV's George Jefferson (who was still a few years away from seeing the televised light of day), and shows readers how Winnie's actions are similar to Mrs. Landon's. Iggie's House powerfully reflects the "white flight" racial tensions of its time but ends on a quiet note, gently reminding readers both young and old that modest victories are sometimes the only ones you get.

For further reading, check out everything Judy Blume has ever written. You'll be glad you did. And to see a Glogster-hosted advertising poster I created for Iggie's House, click here.*

Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret by Judy Blume (1970). Atheneum Books for Young Readers/Simon & Schuster; 149 pages; realistic fiction; ages 9-14; ISBN: 0-689-84158-2.

Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret by Judy Blume (1970). Atheneum Books for Young Readers/Simon & Schuster; 149 pages; realistic fiction; ages 9-14; ISBN: 0-689-84158-2.The suburb of Farbrook, New Jersey, is ex-New Yorker Margaret Simon's new home as she enters sixth grade. She quickly becomes friends with Gretchen, Janie, and Nancy, who invite her into a secret club for girls only; they create Boy Books, listing who they like the most (Philip Leroy is always number one), but mostly they talk about exercises to increase their "bust" and promise to tell each other when they get their periods. Margaret also talks to God about anything and everything, but because her father is Jewish and her mother is Christian, they haven't pressured her to choose between the two. The same can't be said for her overbearing Christian grandparents, but at least Margaret's Jewish grandmother isn't the kind to make her choose sides.

In a way Judy Blume picks up where she left off with her previous novel, Iggie's House, expanding her scope in Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret to incorporate preteen girls' concerns and curiosity about their changing bodies as well as issues of religious faith and tolerance. Blume switches from the third-person narration of Iggie's House to first-person narration in this book, causing the reader to feel Margaret's frustration right alongside her as she questions her body, her beliefs, and everything in between. I especially like how Blume portrays grandparents in her books: Margaret's Jewish grandmother treats her like a person, not a child, similar to the grandmother of Katherine, the protagonist in Blume's 1975 novel Forever.... (Please wait a few years before you tackle that book, tween readers. Having said that, I'm completely positive you won't wait to find out why you should wait.)

For further reading, check out It's Not the End of the World, Blume's 1972 novel about a girl whose parents don't have the same loving bond as Margaret's.

Then Again, Maybe I Won't by Judy Blume (1971). Yearling/Random House; 164 pages; realistic fiction; ages 9-14; ISBN: 0-440-48659-9.

Then Again, Maybe I Won't by Judy Blume (1971). Yearling/Random House; 164 pages; realistic fiction; ages 9-14; ISBN: 0-440-48659-9.A year after Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret Judy Blume published the flip-side male version. Similar to Margaret, Tony Miglione moves from a small house in Jersey City to a big one in (fictional) Rosemont, New York, after his dad, an electrician and part-time inventor, strikes it rich with a prototype for an electrical cartridge. The seventh grader enjoys certain aspects of the 'burbs, like his next-door neighbor Joel's older sister, Lisa, who undresses in front of her bedroom window but doesn't know Tony can see her from his bedroom (or does she?).

On the other hand, he hates that his mom suddenly only seems to care about impressing the Migliones' wealthy neighbors, and he really hates that their new housekeeper has banished his grandmother from the kitchen, depriving her of her main source of happiness. Tony also has to contend with Joel, who's "nice" around adults but shoplifts whenever he can in front of his new friend, which literally ties Tony's stomach in knots.

I first read Then Again, Maybe I Won't when I was in second or third grade. At that time I had no idea what a wet dream was, and I still don't think I knew by fourth grade, but age nine seems like a good entry point for new readers of Blume's classic book. Unlike Margaret and her friends, Tony doesn't talk with other boys about the changes their bodies are going through, including the erections he gets from out of nowhere during school, but his dad does try to have "the talk" with him, and much awkwardness ensues. Then Again, Maybe I Won't proved that Judy Blume could write just as incisively about the young male mind as she could about girls like Margaret and Winnie.

For further reading, check out The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger (1951), featuring another male protagonist who's wary of "phonies." (Recommended for older tweens.)

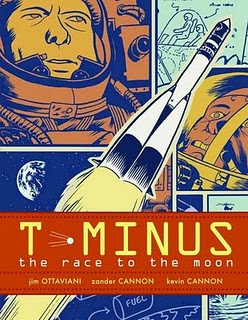

T-Minus: The Race to the Moon by Jim Ottaviani, Zander Cannon, and Kevin Cannon (2009). Aladdin/Simon & Schuster; 124 pages; historical fiction; ages 9-13; ISBN: 978-1-4169-4960-2.

T-Minus: The Race to the Moon by Jim Ottaviani, Zander Cannon, and Kevin Cannon (2009). Aladdin/Simon & Schuster; 124 pages; historical fiction; ages 9-13; ISBN: 978-1-4169-4960-2.A graphic novel covering the historic race between the United States and Soviet Union to put a man on the moon, T-Minus gives equal coverage to both superpowers, culminating in the events of July 20, 1969.

Along the way readers are introduced to the men and women who made it happen, including lesser-known figures like German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, who designed the Saturn V rocket that carried Neil Armstrong and company into outer space; Sergei Korolev, the "chief designer" of the Soviet space program; NASA engineers Caldwell "C.C." Johnson and Max Faget; and "computers," otherwise known in the USSR as Russian women who were hired for their mathematical expertise.

Jim Ottaviani, the writer of T-Minus, and Zander Cannon and Kevin Cannon, who illustrated it (and aren't related, it turns out), stuff a large amount of historical and technological information into T-Minus's 100-plus pages, so much so that at times the pace flagged because I got bogged down in explanations of acronyms such as TLI ("Trans-Lunar Injection") and GUIDO ("Guidance Officer"). If you've recently developed a casual interest in the history of space exploration, T-Minus probably isn't the place to start, but its authors show a deep respect for the attention spans of their intended tween audience, which is to be commended.

For further reading, check out Laika by Nick Abadzis (2007). And to see a Glogster-hosted advertising poster I created for T-Minus, click here.*

No Girls Allowed by Susan Hughes (2008). Illustrated by Willow Dawson. Kids Can Press; 80 pages; history; ages 9-12; ISBN: 978-1-55453-177-6.

No Girls Allowed by Susan Hughes (2008). Illustrated by Willow Dawson. Kids Can Press; 80 pages; history; ages 9-12; ISBN: 978-1-55453-177-6.Susan Hughes's graphic novel, subtitled "Tales of Daring Women Dressed as Men for Love, Freedom and Adventure," is made up of seven stories based on historical fact (more or less) that stretch from 1500 BCE to the American Civil War. Readers learn about Hatshepsut's rise to power as an Egyptian pharaoh despite men only being allowed to hold that title; Mulan's selfless enrollment in the Chinese army, an action she took to save the life of her elderly father; Ellen Craft's bold plan to escape her life as a slave in the American south in the 1840s with her husband, William, also a slave; and four other females who sacrificed their identities but never their souls in order to carve out better lives for themselves.

Hughes crams a lot of history and exposition into her seven tales, sometimes with a heavy hand that also ends stories abruptly, but Willow Dawson's clean black-and-white drawings help convey the characters' fears, frustrations, and triumphs quickly and effectively. "Allowed the freedom to reach out and try, they could achieve their goals," Hughes writes in No Girls Allowed's afterword. "Unfortunately, they had to do it while living a lie." Luckily, their shining examples of courage and independence blazed the trail for countless other women in the years to come.

For further reading about risk-taking females, check out T-Minus author Jim Ottaviani's Dignifying Science: Stories About Women Scientists (1999).

Lafcadio, the Lion Who Shot Back by Shel Silverstein (1963). HarperCollins; 112 pages; humor; ages 9-12; ISBN: 0-06-025675-3.

Lafcadio, the Lion Who Shot Back by Shel Silverstein (1963). HarperCollins; 112 pages; humor; ages 9-12; ISBN: 0-06-025675-3.An African jungle lion decides one day that he isn't going to run from the rifle-carrying hunters who are chasing him and his friends. He tries to make nice with one of them, but when the hunter tries to shoot him, the lion eats the hunter and takes his rifle. Eventually he learns how to pull the trigger with his tail and becomes an expert marksman, attracting the attention of a circus owner who names the lion Lafcadio and brings him to America. Lafcadio becomes rich and famous showing off his skills in front of circus crowds, but when he returns to the jungle years later he questions his place in the world.

Shel Silverstein narrates Lafcadio, the Lion Who Shot Back as "Uncle Shelby," a self-described "very handsome and very intelligent and very kind" man who helps Lafcadio when he arrives in America. The author fills his story with whimsical conceits, such as a suit made of marshmallows and a lion who can sign six autographs at once using his tail, teeth, and four paws, but Lafcadio and his lion friends do eat the hunters who want to shoot them, and those hunters do shoot and kill the lions who don't run away fast enough. Silverstein's book also ends on a down note, with Lafcadio facing an identity crisis—"And he didn't really know where he was going, but he did know he was going somewhere, because you really have to go somewhere, don't you?"—that will likely ring true with tween readers who feel stuck at the border between childhood and adolescence.

Older tweens may also be interested in reading Brian K. Vaughan's graphic novel Pride of Baghdad (2006), illustrated by Niko Henrichon.

Roberto Clemente: Pride of the Pittsburgh Pirates by Jonah Winter (2005). Illustrated by Raúl Colón. Atheneum Books for Young Readers/Simon & Schuster; 40 pages; biography; ages 7-11; ISBN: 0-689-85643-1.

Roberto Clemente: Pride of the Pittsburgh Pirates by Jonah Winter (2005). Illustrated by Raúl Colón. Atheneum Books for Young Readers/Simon & Schuster; 40 pages; biography; ages 7-11; ISBN: 0-689-85643-1.Jonah Winter’s biography of Roberto Clemente, who played baseball for the Pittsburgh Pirates for the duration of his 18 seasons in the major leagues, is a compelling portrait of a man who worked relentlessly at the sport he loved (“’If you don’t try as hard as you can,’ he said, / ‘you are wasting your life’”), using his earnings to give back to the people of his native Puerto Rico before his untimely death in a plane crash on December 31, 1972.

Winter gives his text the appearance of poetry by putting a space between every two lines, thus implying that Clemente was poetry in motion, a hitter, runner, and fielder without equal. Meanwhile, illustrator Raúl Colón alternates soft, cool watercolors with black-and-white pencil etchings, but the latter are only used when showing Clemente in his Pirates uniform, far from home and fighting to be seen as more than just a color. Fans quickly warmed to him, but “the newspaper writers did not,” Winter writes; “when Roberto got angry, / the mainly white newsmen called him a Latino ‘hothead.’”

This hint of a temper is the only negative trait Winter allows his hero, and it’s viewed merely as a byproduct of his quest to become so good at his profession that he could no longer be ignored by the world at large. Winter's message to young readers in Roberto Clemente is that success isn’t guaranteed for anyone in America, but if your work ethic is solid and you keep striving to be the best, you can ultimately prove your doubters wrong.

For further reading, check out Jonah Winter's picture books ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends and Fair Ball! 14 Great Stars from Baseball’s Negro Leagues, as well as the Colón-illustrated Play Ball!, New York Yankees catcher Jorge Posada's account of his childhood in Puerto Rico.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie (2007). Illustrated by Ellen Forney. Little, Brown and Company; 230 pages; realistic fiction; ages 12 and up; ISBN: 978-0-316-01369-7.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie (2007). Illustrated by Ellen Forney. Little, Brown and Company; 230 pages; realistic fiction; ages 12 and up; ISBN: 978-0-316-01369-7.Arnold Spirit Jr. is an awkward but creative 14-year-old Spokane Indian who lives on a reservation with his parents and grandmother. On the first day of ninth grade at the "rez" school, he discovers his mother's maiden name in his "new" geometry textbook. Infuriated, he throws the book at his teacher, breaking the man's nose, but when the teacher comes to Arnold's house to talk to him about the incident, he encourages Arnold to do whatever he can to get off the reservation, before it kills his spirit. Arnold decides to enroll at the all-white high school in nearby Reardan, angering many Indians, especially his newly former best friend, Rowdy, who feels abandoned but can only express himself with his fists. But over the course of the school year, as he experiences one family tragedy after another amidst personal triumphs on the school's basketball court, Arnold comes to terms with his status as a part-time Indian.

Sherman Alexie's semiautobiographical novel is bursting with brash humor and unexpected tragedy (apparently seven of his relatives died in a single school year when he was around Arnold's age). It also doesn't pull any punches in discussing extreme poverty among Indians or the rampant alcoholism that's a direct cause—and effect—of that poverty. Ellen Forney's line drawings enhance Alexie's prose, so much so that it's hard to imagine the book without them. The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian lives up to the critical hype.

Winner of the 2007 National Book Award for Young People's Literature. For further reading, check out The Skin I'm In by Sharon G. Flake or American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang (see below). And to see a Glogster-hosted advertising poster I created for Part-Time Indian, click here.*

The Skin I'm In by Sharon G. Flake (1998). Jump at the Sun/Hyperion; 171 pages; realistic fiction; ages 11 and up; ISBN: 978-142310385-1.

The Skin I'm In by Sharon G. Flake (1998). Jump at the Sun/Hyperion; 171 pages; realistic fiction; ages 11 and up; ISBN: 978-142310385-1.Seventh grader Maleeka Madison is picked on because of the darkness of her skin. When a new language-arts teacher named Miss Saunders arrives at her inner-city middle school as part of a corporate program that puts advertising executives in classrooms for a year, Maleeka finds herself in the presence of a caring mentor, though she doesn't know it at first. In fact she resists Miss Saunders's attention and concern almost every step of the way, partly because the new teacher has a large white birthmark on her black face, making her, in Maleeka's mind, as much of a target for negative comments as Maleeka herself. The protagonist must also deal with an aggressive classmate named Charlese, who lets Maleeka wear her fashionable clothes in exchange for doing Charlese's homework every night.

Author Sharon G. Flake makes the point of providing hints as to how a "bad girl" like Charlese came to be: we see that her home life consists of no parents and an older sister who throws parties that last entire weekends. We also learn why John-John, one of Maleeka's worst verbal tormentors, began disliking her in the first place. The Skin I'm In wraps up its various plot threads a little too neatly (did Maleeka really have to find romance with the cutest boy in school?), but Flake energizes her story as a whole by telling it in Maleeka's urban-teen vernacular ("I ain't no squealer. Never was, never will be."), and her account of a near-rape that Maleeka narrowly escapes is told with vivid, heart-rending suspense.

Winner of the Coretta Scott King Book Awards' John Steptoe New Talent Award in 1999. For further reading, check out The First Part Last by Angela Johnson (see below).

American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang (2006). First Second; 235 pages; drama/fable; ages 12 and up; ISBN: 1-59643-208-X.

American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang (2006). First Second; 235 pages; drama/fable; ages 12 and up; ISBN: 1-59643-208-X.Three stories converge in an unexpected fashion in this graphic novel centering on identity crisis and self-respect. The reader is first introduced to the Monkey King, a character from epic Chinese literature who emerges from a large rock and uses Taoist teachings to gain supernatural powers. But when he attends a party in heaven and isn't given what he considers proper respect for his godlike status, he beats up all the other deities; his punishment is 500 years' imprisonment trapped under a mountain. The second story revolves around Jin Wang, a Taiwanese-American middle schooler who's recently moved from San Francisco to a new town and new school and just wants to fit in, while the third story begins as a sitcom parody entitled "Everyone Ruvs Chin-Kee," in which handsome white teenager Danny is visited—and humiliated—by Chin-Kee, his cousin from China who embodies every outdated Chinese stereotype in existence.

Yang's bold color palette signals an assured sense of identity that generally eludes Jin Wang, Danny, and the Monkey King as they struggle to break free from their roots ("It's easy to become anything you wish," a mysterious Chinese herbalist tells a young Jin Wang, "so long as you're willing to forfeit your soul"). Yang is an inventive storyteller, playing around with readers' preconceived notions of story structure in order to catch them off guard when he delivers his plot twists, and his story ends on a sweetly reconciliatory note. American Born Chinese teaches an important lesson about tolerance—of other people, of your own race, and of yourself—while also throwing in some pee and fart jokes for reluctant male readers.

A 2006 National Book Award finalist in the category of Young People's Literature; also, winner of the 2007 Eisner Award for Best Graphic Album (New). For more fantastical—not to mention fantastic—tales by Gene Luen Yang, check out The Eternal Smile: Three Stories, coauthored with Derek Kirk Kim (2009).

The First Part Last by Angela Johnson (2003). Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers; 144 pages; realistic fiction; ages 12 and up; ISBN: 978-1-4424-0343-7.

The First Part Last by Angela Johnson (2003). Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers; 144 pages; realistic fiction; ages 12 and up; ISBN: 978-1-4424-0343-7.Bobby is 16, a good student who's planning to attend college. He's also a single father. Feather is the baby's name, and Nia is the mother, and we find out why she's no longer around as Angela Johnson's narrative unfolds, crisscrossing back and forth in time as it covers various events that have occurred in Bobby's life. Nia and he are presented with the option of giving Feather up for adoption, but once their lives are changed forever, Bobby decides to bring Feather home—to his mom's home, that is, and despite being a loving, attentive grandmother, she has no intention of taking care of Feather whenever her son is too tired or too busy with schoolwork to do it himself.

The "tough love" reticence Bobby's mother displays as she adamantly refuses to let him deflect any of his parental responsibilities onto her, is my favorite aspect of The First Part Last. It's nice to see a pregnancy-centered "problem" novel for tweens and teens that's told from the father's perspective—one who doesn't leave the hard work to the mother—but the revelation of why Nia isn't around tips the story into soap-opera territory, and the conclusion pours on the schmaltz. Still, the novel's good qualities outweigh the bad.

Winner of the 2004 Michael L. Printz Award and 2004 Coretta Scott King Award. For further reading, check out Angela Johnson's Heaven (1998), another Coretta Scott King Award winner, in which Bobby makes his first appearance.

The Death of Superman by Dan Jurgens, Jerry Ordway, Louise Simonson, and Roger Stern (1993). Illustrated by Jon Bogdanove, Tom Grummett, Jackson Guice, Dan Jurgens, et al. DC Comics; 168 pages; sci-fi/fantasy; ages 8-13; ISBN: 1-56389-097-6.

The Death of Superman by Dan Jurgens, Jerry Ordway, Louise Simonson, and Roger Stern (1993). Illustrated by Jon Bogdanove, Tom Grummett, Jackson Guice, Dan Jurgens, et al. DC Comics; 168 pages; sci-fi/fantasy; ages 8-13; ISBN: 1-56389-097-6.This graphic novel delivers on its promise: the seemingly immortal Man of Steel is killed at the hands of Doomsday, an otherworldly creature more powerful than any foe he's faced before. Doomsday is a killing machine, pure and simple, whose agenda consists of nothing more than total annihilation of everything that lies in his path.

Because The Death of Superman is a compilation of seven comic-book issues that spanned five different DC Comics titles (Superman, Superman: The Man of Steel, The Adventures of Superman, Action Comics, and Justice League America) at the tail end of 1992, there's a bit of repetition in the storytelling to fill in readers who may not have picked up previous issues. Every few pages it seems like a new character is questioning the origins of Doomsday, just as Superman constantly questions his ability to defeat the creature. The action-packed Doomsday story line, which becomes increasingly bloody as it nears its climax, starts on an unpromising note with a subplot involving creatures who live below the streets of Metropolis, but once Superman is interviewed on a local daytime talk show and states that "violence is the price we pay to accomplish a greater good," The Death of Superman begins to take off.

For further reading, check out World Without a Superman and The Return of Superman, which completed the saga in 1993.

Weetzie Bat by Francesca Lia Block (1989). HarperCollins; 109 pages; magical realism; ages 12 and up; ISBN: 978-0-06-073625-5.

Weetzie Bat by Francesca Lia Block (1989). HarperCollins; 109 pages; magical realism; ages 12 and up; ISBN: 978-0-06-073625-5.Weetzie grew up in Los Angeles and is nostalgic for a Hollywood she never knew, yet it's one we all unconsciously know, the golden age of stars like Bogart and Monroe. Weetzie is in her early 20s and a little lost when she meets Dirk, who becomes her new best friend. Dirk's gay, and Weetzie helps him in his search for an ideal boyfriend. Together they find Duck, while Weetzie falls for the one and only Secret Agent Lover Man. The two couples then move in together, but author Francesca Lia Block doesn't provide them with "happily ever after" until she's thrown a wrench or two into the works, plus a baby, a disease, and a death or two.

If you're in the right frame of mind, Weetzie Bat is a fun read that operates mostly on dream logic as it blends elements of 1980s L.A. with 1950s La-La Land. Tweens and teens discovering the book today can learn a little about the AIDS epidemic that permanently changed the American landscape in the '80s for both homosexuals and heterosexuals, though Block's then-progressive scenario of a woman and her two gay male friends raising a baby together may seem quaint to today's younger audiences. Thank God for that ...

For further reading, check out subsequent entries in Block's "Dangerous Angels" series: Witch Baby, Cherokee Bat and the Goat Guys, Missing Angel Juan, and Baby Be-Bop.

Coolies by Yin (2001). Illustrated by Chris Soentpiet. Philomel/Penguin Putnam Books for Young Readers; 40 pages; history; ages 7-10; ISBN: 0-399-23227-3.

Coolies by Yin (2001). Illustrated by Chris Soentpiet. Philomel/Penguin Putnam Books for Young Readers; 40 pages; history; ages 7-10; ISBN: 0-399-23227-3.Shek and his younger brother, Wong, leave famine-devastated China for America in the mid-1800s to find work building the First Continental Railroad along the western portion of the country. Their goal is to send money home so their remaining family members won't starve. On top of back-breaking work and discrimination from white railroad foremen, who condescendingly call the Chinese "coolies," or slaves, Shek, Wong, and their fellow immigrants discover they're being paid less than non-Chinese laborers. They go on strike, but Shek reminds them that as long as they don't work, they can't send money back to their families in China.

Yin tells her story with a framing device involving a tween boy and his grandmother, who regales him with the history of her great-grandfather and his brother—Shek and Wong, respectively. Soentpiet's drawings employ wide-screen, sun-kissed vistas that add cinematic flair to Yin's heartfelt, human prose. "Call us what you will," Shek says upon the completion of the First Transcontinental, "it is our hands that helped build the railroad."

For further reading, check out Ten Mile Day and the Building of the Transcontinental Railroad, written and illustrated by Mary Ann Fraser (1993).

Debbie Harry Sings in French by Megan Brothers (2008). Henry Holt and Company; 234 pages; realistic fiction; ages 13 and up; ISBN: 978-0-8050-8080-3.

Debbie Harry Sings in French by Megan Brothers (2008). Henry Holt and Company; 234 pages; realistic fiction; ages 13 and up; ISBN: 978-0-8050-8080-3.This coming-of-age novel centers on Johnny, a 1990s Florida teen whose dad dies in a car crash the week of his 13th birthday. His mom, too depressed to do much of anything over the next couple years, leaves chores like shopping for groceries and paying the bills to Johnny; he starts drinking to deal with the pressure. After she recovers and takes charge of the household again, Johnny accidentally overdoses on Ecstasy one night at a club. He goes into rehab, but following his own recovery, his mom sends him to South Carolina to live with his uncle Sam, whereupon he meets and falls for Maria, a “bad girl” who shares his love of 1970s punk rock (Blondie, Patti Smith, the Ramones) and helps Johnny explore his latent interest in transvestism.

Debbie Harry Sings in French received a starred review from Publishers Weekly for its “brisk pace and ... strong-willed, empathetic narrator,” although, like Kirkus Reviews, it took issue with Brothers’s plot, which the latter found “problematic,” especially in the early chapters set in Tampa. I’m sure a movie adaptation would cut the bulk of those chapters, but I enjoyed how Brothers presented a single-parent household in which the only child, out of sheer necessity, takes on the responsibilities of the incapacitated parent. Booklist’s Jennifer Hubert noted that “the prose occasionally slides into cliché,” but I’d argue it’s the supporting characters who sometimes run the risk of being stereotypes: Lucas, the hip, wise Jamaican record store owner, skirts the edge of “Magical Negro” status, and Bug, Johnny’s female cousin, acts more like a precocious second grader than an 11-year-old on the cusp of adolescence.

For further reading, check out Parrotfish by Ellen Wittlinger (2007).

Twelve Rounds to Glory: The Story of Muhammad Ali by Charles R. Smith Jr. (2007). Illustrated by Bryan Collier. Candlewick Press; 80 pages; biography; ages 9-14; ISBN: 978-0-7636-1692-2.

Twelve Rounds to Glory: The Story of Muhammad Ali by Charles R. Smith Jr. (2007). Illustrated by Bryan Collier. Candlewick Press; 80 pages; biography; ages 9-14; ISBN: 978-0-7636-1692-2.Charles R. Smith Jr.'s picture-book biography of the legendary boxer is written as a series of poems, simultaneously emulating and paying tribute to its subject, whose famous pre-fight poems—"Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee / His hands can't hit what his eyes can't see"—influenced the braggadocio of early rap music. Warmly illustrated by Bryan Collier, Twelve Rounds to Glory takes young readers through Ali's entire career, from his heavyweight-championship knockout of Sonny Liston in 1964 to his refusal to fight in the Vietnam War three years later, and continuing on to his popular and professional comeback in '74, when he beat his seven-years-younger opponent, George Foreman, to regain the heavyweight title. The book ends with a brief mention of Parkinson's disease, which Ali was diagnosed with in 1984.

Smith doesn't ignore the often ugly insults Ali slung at his opponents before fights, the worst of them reserved for Joe Frazier: "cutting even deeper / into his heart by dropping a bomb, / by insulting his blackness when you called him Uncle Tom." But for the most part this is a sunny-side-of-the-street biography, in which Ali's four marriages and eight children, two of which were born out of wedlock, are treated as a show of generosity on Ali's part, i.e., he had too much love for just one family! Smith's poetry shines brightest when he recounts Ali's various title bouts, including the 1974 "Rumble in the Jungle" versus Foreman in Zaire: "'IS THAT ALL YOU GOT? / IS THAT ALL YOU GOT?' / absorbing brick after brick, / taking shot after shot, / infuriating the Bull, / making his eyes see blood-red, / moving shots to the body / up top to the head."

Winner of Honor Book recognition from the Coretta Scott King Book Awards in 2008. For more of Smith's poetry, check out the basketball-themed Hoop Kings (2004). And to see a book trailer I created for Twelve Rounds to Glory, click here.

In His Own Write by John Lennon (1964). Simon & Schuster; 79 pages; humor; ages 10 and up; ISBN: 0-684-86807-5.

In His Own Write by John Lennon (1964). Simon & Schuster; 79 pages; humor; ages 10 and up; ISBN: 0-684-86807-5.The Beatles stormed America in 1964 after conquering their native UK, so it made sense that any of the band's side projects would generate at least some interest from fans and the general public. Hence In His Own Write, singer-guitarist John Lennon's debut collection of stories, poems, and drawings, some of which were generated during his school days in Liverpool, or "Liddypool," as he refers to his hometown in a short story of the same name. "The writing Beatle," as one particular version of the book's cover touts, enjoys playing around with pronunciations and spellings, as evidenced by titles like "The Fingletoad Resort of Teddiviscious" and "On Safairy With Whide Hunter" ("written in conjugal" with Paul McCartney). He also isn't afraid to explore dark territory, a la Roald Dahl: in "The Fat Growth of Eric Hearble," the title character loses his job "teaching spastics to dance" and is called a "cripple" because of the scabby growth on his head that has conversations with him, and in "Randolf's Party" the protagonist is killed by his friends at his own "Chrisbus" gathering.

I was somewhat surprised to find In His Own Write in the Young Adult section of the Oak Park Public Library, but because Lennon's stories and poems are almost exclusively short and nonsensical, I can see the appeal for younger readers. However, because of Lennon's inventive spellings and heavy use of English slang, some of which may have gone out of fashion about the same time the Beatles broke up 41 years ago, In His Own Write can be a frustrating read. Beatles fans of all ages are encouraged to give it a go all the same: famous Lennon song lyrics like "Yellow mother custard dripping from a dead dog's eye" aren't far removed from poem lyrics such as "I wandered hairy as a dog / To get a goobites sleep" ("I Wandered").

For further reading, check out Lennon's second collection of this and that, A Spaniard in the Works, published the following year. And to see a book trailer I created for In His Own Write, click here.

* Glogster is a temperamental beast. At a certain point I had to give up on making all of the text I created completely visible at all times. What you see is what I got.

Wednesday, December 21, 2011

kinda sorta film reviews for tweens and teens (i.e., movies I watched this year and wrote about for school)

The longtime DC Comics superhero makes his big-screen debut in this special-effects extravaganza. Test pilot Hal Jordan knows how to fly a fighter jet better than almost anyone, but he's reckless and cocky, and can't shake the memory of watching his father die in a plane crash when Hal was just a boy. Millions of light years away, Abin Sur, a member of the intergalactic Green Lantern Corps (think of them as the space police), is mortally wounded fighting Parallax, a yellow mass of energy that turns out to be the physical embodiment of fear itself. Abin Sur crash-lands on Earth and gives his green power ring to Jordan, who is then indoctrinated into the Green Lantern Corps on their home planet of Oa and learns how to use his ring to create anything he can see in his mind, including giant machine guns and catapults. Jordan will have to overcome all his fear if he's to prevent Parallax from destroying humankind.

Green Lantern was considered a box-office disappointment soon after it opened last June, and the critics weren't too kind, but I thought it was more entertaining than Thor, which debuted a month earlier to more enthusiastic audiences. All the money that went into the special-effects budget appears to be on the screen, especially in the scenes set in outer space, and Parallax is a vaguely defined but impressive-looking villain. But after Robert Downey Jr.'s snarky portrayal of Tony Stark in the two Iron Man movies, Ryan Reynolds's similar approach demonstrates the law of diminishing returns. (Peter Sarsgaard, as pseudovillain Hector Hammond, seems to be having the most fun out of all the actors.)

For further viewing, check out Batman Begins (2005) and The Dark Knight (2008), two films that demonstrate just how good superhero movies can be.

Fourteen-year-old Joe Lamb's mother has died in a factory accident, and four months later he and his father, a local sheriff's deputy, are still grieving in their own separate ways while drifting further apart from each other. Joe's friend Charles is making a zombie movie on his Super-8 camera—the film is set in the summer of 1979—and asks Joe to apply makeup to the actors. Joe is happy to oblige since this means he'll get to talk to—and lightly touch the face of—Alice, a classmate who's agreed to play the hero's wife in Charles's movie. But when Charles and his middle-school crew go to a long-abandoned train depot to film a scene late one night, they witness a train derailment that unleashes an alien creature.

Super 8 was conceived by writer-director J.J. Abrams as a nostalgic tribute to Steven Spielberg films of the late '70s and early '80s like Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T., although the alien in Super 8 is a whole lot meaner than any of the ones in those films. The first half of the film, like E.T., has charm to burn—it's fun to watch Charles and Joe work on their zombie movie, and touching how Joe and Alice bond while Charles realizes Alice is interested in his friend, not him—but the second half is more about action and chase scenes than anything else, recalling 1985's The Goonies, which Spielberg produced but didn't direct (I didn't see it until I was 28, so the whole movie just felt like one long sequence of kids screaming). I was ultimately disappointed in Super 8—and since Abrams was a teenager himself in 1979, how come he uses insults and expressions like "douche" and "awesome," which weren't around back then, into his script?—but I think tweens will enjoy the thrill ride as much as the tender moments, if not more so.

For further viewing, check out Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982).

Fred: The Movie (Nickelodeon, 2010). Directed by Clay Weiner; teleplay by David A. Goodman; 80 minutes; comedy; ages 6-12.

Although Fred is technically a teenager, he's played by Lucas Cruikshank (who originally created the character for a series of YouTube videos) as if he's a hyperactive six-year-old, which is probably the average age of Fred's most ardent admirers. They're the ones who are most likely to appreciate his near-constant screaming and childish tantrums in this made-for-TV movie, though Cruikshank provides genuine laughs in a dual role as Derf, a stoic, monotone teen Fred meets on the bus; in other words, he's Fred's exact opposite. Saturday Night Live veteran Siobhan Fallon is also good as Fred's exhausted mom, and Jake Weary has impressive comic timing as Kevin, so the movie's not a complete wash for adults, but if you have kids who want to run Fred: The Movie on a constant loop, it's going to wear out its welcome sooner rather than later.

For further viewing, check out Tim Burton's directorial debut, Pee-wee's Big Adventure (1985), whose title character's extreme man-child personality may not appeal to everyone, but at least he's surrounded by lots of great jokes and sight gags.

Pistachio Disguisey is a put-upon waiter in his family's Italian restaurant, unaware that his father and grandfather and so on are retired Masters of Disguise. When his father, Fabbrizio, is kidnapped by an evil rich dude who forces Fabbrizio to steal priceless artifacts like the U.S. Constitution so Bowman can later sell them to the highest bidder, Pistachio is called into action by his grandfather, who teaches him the ancient family art of disguise. He'll need an assistant if he's going to locate his father, though, so Pistachio hires Jennifer, a single mom whose grade-school son has taken a shine to Pistachio.

The Master of Disguise is rated PG, but it contains a few smutty sex jokes that are out of place among the constant barrage of silly voices and costumes deployed by star Dana Carvey, who reportedly came up with the idea for the film because he wanted to make a movie his kids could watch. Sadly, The Master of Disguise fails to entertain on almost every level, with Carvey, who was so good at playing all kinds of characters and doing various impressions on Saturday Night Live from 1986 to '93, a pale imitation of his former self. (Fred: The Movie is a masterpiece compared to this turkey.)

It's possible younger kids will eat up the wall-to-wall silliness, and they'll recognize Maria Canals-Barrera, the mom from Wizards of Waverly Place, before they recognize Carvey from anything, but they still might wonder why the end credits last an astonishing ten minutes and are filled with outtakes from scenes that don't otherwise appear in the movie, which only lasts a scant 70 minutes before the credits kick in. Can you say "a huge mess," kids?

For further viewing, check out Wizards of Waverly Place: The Movie (2009).

In 3028 A.D., Earth is blown to bits by an intergalactic race called the Drej (the "A.E." in the film's title stands for "After Earth"), but not before Professor Sam Tucker launches the Titan, a mobile lab that has the components needed to create a new planet—if it can be found in deep space before all that's left of humanity is wiped out. Mankind is now a minority species in the universe, subsisting in assorted drifter colonies. Tucker's son, Cale, was a boy when Earth was destroyed; Captain Korso, who claims to have known the professor, finds Cale and shows him that the ring his father gave him right before he launched the Titan and disappeared forever contains secret directions that can help them locate the lab. The Drej hope to locate it too—and destroy it, sealing mankind's fate.

Over the years I'd heard good things about Titan A.E., which disappeared quickly from theaters in the summer of 2000. I'm sure tweens will find it at least somewhat entertaining, but I thought its mix of old-school hand-drawn animation and new-school computer animation was jarring, as if directors Don Bluth and Gary Goldman or the studio couldn't make up their minds on which way to go. A chase sequence set among asteroid-sized reflective icicles is beautifully rendered, but in most other instances it looks like the animators overdid the hand-drawn material—characters' faces are constantly in motion, as if they're all on Ritalin—while underbudgeting the necessary computer effects. Worse, the story line is highly derivative of Star Wars at times (not to mention Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and even Waterworld), with Cale and Korso performing a mediocre Luke-and-Han tribute act.

For further, better animated viewing, check out Pixar's WALL-E (2008).

Set in the early 1970s, Crooklyn is episodic in nature and therefore won't appeal to everyone, but because it's semi-autobiographical—oldest brother Clinton appears to be based on cowriter-director Spike Lee, and Troy seems to represent cowriter Joie Susannah Lee (both have cameos in the film)—the Carmichael house feels like it's actually been lived in, not constructed for use in a movie. The Carmichael kids are almost always yelling and fighting with each other about something, but unlike the kids on Hannah Montana, for instance, their fights aren't constructed around well-rehearsed one-liners. And when the Carmichaels talk back to their mom, they suffer the consequences right away.

Set in the early 1970s, Crooklyn is episodic in nature and therefore won't appeal to everyone, but because it's semi-autobiographical—oldest brother Clinton appears to be based on cowriter-director Spike Lee, and Troy seems to represent cowriter Joie Susannah Lee (both have cameos in the film)—the Carmichael house feels like it's actually been lived in, not constructed for use in a movie. The Carmichael kids are almost always yelling and fighting with each other about something, but unlike the kids on Hannah Montana, for instance, their fights aren't constructed around well-rehearsed one-liners. And when the Carmichaels talk back to their mom, they suffer the consequences right away.The last 20 minutes of Crooklyn may be too intense for younger viewers in the same way that Doris Buchanan Smith's book A Taste of Blackberries was too intense for me when I was eight years old. But it's a hell of an ending, one that makes me cry every time I watch the film. (Another selling point is Crooklyn's wall-to-wall soundtrack of early-'70s R&B hits, including the Spinners' "Mighty Love," Jean Knight's "Mr. Big Stuff," and Stevie Wonder's "Signed Sealed Delivered I'm Yours.")

For further viewing, check out Akeelah and the Bee (2006). And to see a trailer for Crooklyn, click here.

High school senior Ferris Bueller, a kid who gets away with everything, wants to skip school, and he wants his girlfriend, Sloane Peterson, and his uptight best friend, Cameron Frye, to join him in spending the entire day in downtown Chicago. The principal at their school, Ed Rooney, wants nothing more than to catch Ferris in the act, and the same goes for Ferris's sister, Jeanie, who really really really hates that he gets away with everything. Will he make it home in time for dinner without his parents discovering that he lied about being sick? Will Cameron ever loosen up? And will Jeanie resume her brief police-station romance with Charlie Sheen after the movie has ended? (Don't do it, girl. He's trouble.)

I saw Ferris Bueller's Day Off on video when I was 11, the year after it came out, and since I was already a big fan of the TV show Moonlighting, I was pleased as punch to see Ferris "breaking the fourth wall" just like Cybill Shepherd and Bruce Willis did. Now that I'm older, part of me wants to see Ferris taken down a peg, so I sympathize with Jeanie more than I used to, even if she is pretty much a brat. Tweens, on the other hand, will probably still thrill to Ferris's every anti-authoritarian move. On a side note, I always thought it was odd that Ferris Bueller's Day Off didn't have an accompanying soundtrack album—there are so many good songs featured in the film, including the Dream Academy's instrumental cover of the Smiths' "Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want"—but according to an article I once read, writer-director John Hughes didn't think the songs would flow well together as a set. If only iPods had been around in 1986 ...

For further viewing, check out the defunct Nickelodeon series Ned's Declassified School Survival Guide (2004-2007) on DVD.

The Red Balloon, also known as Le Ballon Rouge, centers on a Parisian boy, played by writer-director Albert Lamorisse's son, who discovers the title character tied to a lamppost one morning. He takes it wherever he goes, and soon the balloon is showing signs of life: when the boy's mother tosses the balloon out the window at first glance, it hovers outside instead of floating away until the boy can pull it back in. It also evades the capture of the boy's classmates and schoolteachers, though its fate is never certain. Lamorisse gives his film an uplifting ending in more ways than one, and it's complemented by Maurice Leroux's musical score, which is as wide-eyed as The Red Balloon's protagonist.

There are a few subtitles since the dialogue is in French, but for the most part The Red Balloon is a silent film that relies on visual storytelling above all else, with the balloon turning out to be one of the most memorable characters I've ever seen in a movie. (I'm curious to know how many had to be used in the course of filming.) Lamorisse never panders to his audience, and despite the film's age and subtitles, I think The Red Balloon can be enjoyed by English-speaking tweens of all ages just as long as they show some patience in the early stretches—attention deficit disorder hadn't yet been invented in 1956.

For further viewing, check out another Lamorisse short film with a young male protagonist, White Mane (1953), which is available on a double-feature DVD with The Red Balloon.

And for the grand finale, a kinda sorta musical!

Never Let You Go by Justin Bieber (Teen Island Records, 2010). Directed by Colin Tilley; 4 minutes; pop/R&B; all ages.

In the music video for "Never Let You Go," a track from his 2010 album My World 2.0 (his original world needed a software update, apparently), teen-pop sensation Justin Bieber promises a girl that he will do exactly as the song's title says. But wait! Something's rotten in the state of Denmark! (Or the state of California, anyway, since that's probably where the video was shot.) The girl in question is clearly shown wearing two wristwatches on her left arm, a subtle visual indication that she will eventually two-time our postpubescent-but-still-looks-prepubescent-but-I-guess-that's-why-he's-so-nonthreatening-and-therefore-acceptable-to-moms-everywhere hero.

Say it ain't so! The Beeb keeps reassuring this vixen that he'll never let her go when he's the one who's going to be let go. How tragic. But if he ever needs a shoulder to cry on, I'm sure his doppelganger, actress Leslie Bibb, wouldn't mind lending one. (Bieber ... Bibb ... Bibber? She was born in '73, he was born in '94. The mom math isn't impossible, that's all I'm saying.) But you know what else is tragic? Bieber's song has the same title as New Kids on the Block's final single from 1994, the year he was born and they broke up because their popularity had fallen off the side of a cliff. The fickleness of teen-pop fans can be so cruel.

For further viewing, check out the aforementioned New Kids on the Block music video of the same name, in which tenor Jordan Knight makes it clear that he's no longer nonthreatening.

Monday, December 19, 2011

making ads out of nothing at all

Earlier this month I created the following "book trailers" for an online Materials for Tweens class offered through San Jose State University. Searching for copyright-free photos and audio wasn't easy. You win, public domain.

First up, a promo for Twelve Rounds to Glory: The Story of Muhammad Ali by Charles R. Smith Jr. and illustrator Bryan Collier (2007).

Next, John Lennon's print debut, In His Own Write (1964).

First up, a promo for Twelve Rounds to Glory: The Story of Muhammad Ali by Charles R. Smith Jr. and illustrator Bryan Collier (2007).

Next, John Lennon's print debut, In His Own Write (1964).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)